I am still amazed by those who have the time to maintain a blog. I don't, so the best I can offer here is occasional short bits of news and observations.

I have disabled comments for this site. If you want to discuss Japanese cinema, please join KineJapan, the list for which I serve as co-owner.

Comic Legacies on the Japanese Silver Screen

I have been thinking a lot about Japanese comedy these last few years. It started not just with watching lots of film comedy, but also with going frequently to comedy halls in Japan, from yose vaudeville halls to theaters that feature manzai acts or even stand-up comedy. I taught a course in Japanese comedy in 2022, I put on a live comedy event called Verbal Arts of Japan in 2023, and even did a review of a recent book on rakugo for Monumeta Nipponica.

My most recent endeavor has been to program a series featuring some of the great works of Japanese film comedy. This was not easy to do. While comedy has been a central genre in Japanese film history, few foreign festivals have programmed it and not many scholars have studied it—why is an interesting problem—so there are actually not many English subtitled film prints. The National Film Archive of Japan had a pretty good collection of prewar films, but I had to rely on the Japan Foundation for postwar films. Even then, some of the legendary series like the “Irresponsible” series featuring the Crazy Cats could not be shown because there are no subtitled prints. We also had problems with one of the film companies, which did not give us permission in time, so we had to cancel an Enoken film. Still, we came up with a pretty good set of films.

The Motomiya Movie Theater Poster Champion Festival

One movie theater I want to go to, but have not yet visited, is the Motomiya Movie Theater in Motomiya, Fukushima. Built in 1914, it was originally created as a space for stage plays and public meetings, but was then transformed into a movie theater during the war. Before closing in 1963, it showed a wide variety of movies, many of the B-movie—or lower level—variety. What is fascinating is that the building has not been torn down and is actually still maintained as a movie theater, occasionally showing films and doing special events. It is also supposedly the only theater left in Japan that shows films with a carbon arc 35mm projector. Especially with a very active social media presence (see their Facebook page), the Motomiya Movie Theater still garners a lot of attention, being the subject of documentaries, news reports, and even a book: Basue no shinema paradaisu. It suffered storm damage a couple of years ago, but successfully sold T-shirts to help with repairs (I bought one, of course).

Sapporo Film and Video Equipment Museum / 札幌映像機材博物館

When Markus Nornes and I published the Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies in 2009 (a Japanese translation came out in 2016), we tried to offer in one section a comprehensive guide to facilities for pursing research on film in Japan. A good number of them we regularly utilized, and thus offered our hands-on experience with how to use them, while others we researched by visiting or through other means. As with any synchronic record of the state of a field, a list of such facilities can soon begin to age, as institutions change, appear, or disappear. Some of the places we described sadly no longer exist, but thankfully new institutions have been founded as well. The possibility of a new edition of the Research Guide is very much on our mind, so we regularly visit new places when we can. I sometimes write about them on this blog, such as when I introduced the Ichikawa Kon Memorial Room a while back.

So when I visited Hokkaido this summer, I made a point of scouting out the Sapporo Film and Video Equipment Museum (that's my translation of 札幌映像機材博物館). Originally created in Noboribetsu by a former film cameraman, Yamamoto Bin, it moved to Sapporo last year into a nondescript building in a nondescript section of town in the Shiroishi neighborhood. Not all of it is organized but I tend to agree with the museum head that there is really nothing like this in all of Japan. There are just hundreds of examples of film and video equipment, from cameras, film viewers, editing machines (Steenbecks, etc.), and projectors, to sound recorders, video cameras, and editing decks. There are so many 8mm cameras they are literally in a pile. One of the largest items is a Panther crane. Many of the main items have display descriptions (though in Japanese) to help the visitor understand their significance.

The Benshi as Vaudeville Performer

I am in Japan for the summer doing research and preparing for future projects. As I mentioned when advertising the Verbal Arts in Japan event at Yale, I have been seeing a lot of rakugo in Japanning recent years, especially at yose, the vaudeville halls that feature rakugo in addition to other entertainments such as magic, juggling, voice impersonation, etc. Even though I’ve been going to yose from before COVID, it is possible some of my current attraction is due to the desire to re-experience a communally shared present/presence in physical proximity. But there are research reasons as well, as I have been teaching and researching Japanese comedy as a whole.

It was interesting, however, to see that my interest in film and yose found an object in common this summer: not only the presentation of films in yose, but screening of them with a film benshi. The benshi Sakamoto Raiko, whom I’ve worked with before, joined one of the main rakugo organizations, the Rakugo Geijutsu Kyokai, as an iromono (those who are not rakugoka and appear in yose). I attach his GeiKyo profile above.

Verbal Arts of Japan Comes to Yale

As some of you know, rakugo—Japan’s “sit-down” form of comedic storytelling—has become one of my passions in recent years, as I have frequently been going to yose and other rakugo events whenever I am in Japan. I’ve been to all the main Tokyo yose and even Osaka’s sole yose and have enjoyed performances from a wide variety of rakugoka. The thought occurred ro me about four years ago that I might want to bring some of these brilliant comedians to Yale. Well, after a four-year wait, they are here and will perform on March 30, 2023, at the 53 Wall Street Auditorium at Yale University.

With the splendid assistance of Momoe Melon, who also produced the various editions of Conversations in Silence (here, here, here, and here), we invited some of the top performers in rakugo—plus one of the stars of rokyoku, a sung-form of oral storytelling—to perform in New Haven. After a performance at Yale, the group will do a tour, first going to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and then Dickinson College.

Murakami Haruki: Journey into the Movies

For one reason or another, I have participated in several projects focused on the novelist Murakami Haruki. After being one of Murakami’s hosts when he was given an honorary doctorate at Yale in 2016, I was invited to participate in an international symposium in France in 2018, which then became a book in Japan in 2020 (a French version is supposed to come out, but there’s been no recent news on that). So I was not completely surprised when a curator at Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (fondly known as the Enpaku) asked me to write something for the catalog of an exhibition they were planning on Murakami’s relation to cinema.

Most of Murakami’s long novels have not been made into films, yet there are some splendid cinematic adaptations of his short stories, ranging from Yamakawa Naoto's A Girl She Is 100% (1983) and Ichikawa Jun’s Tony Takitani (2004) to Lee Chang-dong’s Burning (2018) and Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s Drive My Car (2021). What not every Murakami fan knows, however, is that, in addition to inserting a myriad of cinematic references in his novels, Murakami was actually a film studies major at Waseda in college, with plans to become a scriptwriter. He apparently spent a lot of time in the Enpaku reading scripts and even wrote a senior essay on the motif of travel in American cinema. His career eventually moved in a different direction, but he has never strayed too far from cinema.

Obayashi in the Crosshairs

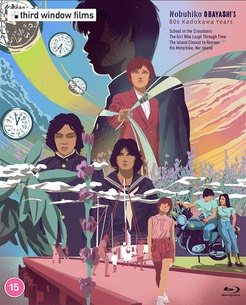

Ever since the director Obayashi Nobuhiko visited Yale in 2015, I’ve been significantly engaged with his cinema in one form or another, from curating a Japan Society retro to starting a book project (which occasioned an Obayashi workshop earlier this fall). This has recently extended to helping out with Blu-ray releases. Adam Torel of Third Window Films asked me last year to pen a piece for the booklet accompanying his release of Obayashi’s Anti-War Trilogy, and then this year asked for help with his release of four Obayashi films from the director's years working with Kadokawa Film. That has now come out in a box set titled Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 80s Kadokawa Years.

There is still relatively little written about Kadokawa in English (Alex Zahlten’s The End of Japanese Cinema is one significant exception), even though the films produced by Kadokawa Haruki—as well as his industrial strategy—helped define Japanese cinema in significant ways from the 1980s on. Given the image of Obayashi as an aesthetic rebel, established through the wild cinema evident in Hausu, it may seem peculiar that Obayashi not only made four films with Kadokawa, but got along with the eccentric producer quite well. Those films might challenge the Obayashi Hausu-image because most were idol movies and, like The Island Closest to Heaven, could have little of the "anything goes" film craft that supposedly defined Obayashi. As such, the Blu-ray releases might help take apart that image and spread understanding of Obayashi as a director of many faces and film styles.

Inventing Television through Film in Japan

It’s taken a while to announce this publication, but it took even longer for it to appear. Wiley-Blackwell’s A Companion to Japanese Cinema, edited by David Desser, was finally published earlier this year, with a piece by me on the relation between cinema and television in the first decade after the start of public broadcasting in Japan. Editing these kind of general handbooks is not an easy task, so I salute David for not only inviting me to participate, but for also managing thirty people writing on very different topics. The list of contributors is like a who’s who of Japanese film studies.

My chapter is a continuation of a number of articles I have written on the early years of television in Japan, particularly my piece "From Film to Television: Early Theories of Television in Japan” in Marc Steinberg and Alex Zahlten’s Media Theory in Japan. If that focused on early theorizations of television in Japan, arguing that efforts to distinguish television often forgot, while also reproduced, some of the claims made about cinema in its first decades, this contribution considers how film was actually a key means by which television was constructed. Pushing back against the often-told history of the film industry’s antagonism against television once broadcasting began in 1953, I show how the industry was not only actively involved in TV, even helping found some of the key networks, but was only antagonistic to the degree television became too much like cinema. The film industry was thus accepting TV as long as it was not a threat, and thus was deeply involved in attempting to form TV as difference. I continue my previous work on TV theory by also arguing that theorists such as Iijima Tadashi, Sasaki Kiichi, and Okada Susumu similarly tried to conceptually police the border between film and television, especially when it came to the practice of using film to make TV programs (a practice called terebi eiga at the time). Distancing myself from claims that the appearance of television led to the conceptualization of “eizo” as modern technological moving images transcending media specificity, I point to Okada’s theorization of TV as “half-image” (han-eizo) as one example of how eizo was repeatedly theorized through difference and distinction. I conclude by speculating about how these attempts to invent television were also efforts to create a new synthetic media which would, at the same time, enable new forms of cinema.

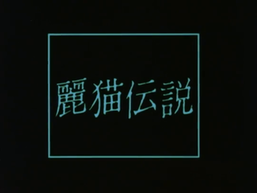

Obayashi Nobuhiko, Ghost Cats, and To Sleep So as to Dream

This last weekend, we held a workshop on the film director Obayashi Nobuhiko at Yale. This was part of a project Aiko Masubuchi, formerly of the Japan Society in New York, and I have been pursuing to publish the first book-length anthology on Obayashi in English. We had a public call for papers and invited those whose proposals were chosen to come to Yale to discuss their papers. It was in the format I like a lot: instead of people just reading their papers, the drafts were distributed beforehand and time was mostly used for discussion. Befitting a director who worked in so many media and genres, there were papers on many different topics by people of quite different backgrounds, with mine focusing on Obayashi’s work in television commercials. Contributors will now re-work their papers and turn in final drafts in the spring.

The workshop was closed to the public, but as its public facing aspect, we screened Obayashi’s TV movie Reibyo densetsu (麗猫伝説: which we provisionally translated as The Legend of the Beautiful Ghost Cat), which he made in 1983 for the Tuesday Suspense Theater slot. The film has come out on DVD in Japan, but it has likely never been shown abroad, so several of us split up the work and made some very rough English subtitles. Obayashi Chigumi, the director’s daughter, was a guest at the workshop, and she made a few comments after the film. It was interesting to hear that the house used in the film is actually the Obayashi family home in Onomichi.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takako_Irie

Noriaki Tsuchimoto Research Grants

With the donation of Tsuchimoto Noriaki’s papers to Yale, we have put together funds to support research using the collection. If you are pursuing research that would make use, at least in part, of the Papers, please consider applying. These grants will be available next year as well.

Noriaki Tsuchimoto Research Grant

水俣シリーズなどで有名なドキュメンタリー映画作家・土本典昭の個人資料が、アメリカのイェール大学図書館に寄贈されました。昨年度にようやく整理がほぼ完了し、研究者による閲覧が可能となりました。土本監督が携わった作品の台本、準備から制作にいたる資料などを含む土本典昭コレクションの活用を促進するために、この度イェール大学の東アジア研究所は、「土本典昭助成金」を設けました。今後の2年間、イェール大学への渡航費など、各年4名の研究者に助成します。助成金の初年度の申請を現在募集中であり、締め切りは2022年8月31日です。コレクションの内容や申請方法の詳細は下記の英文に明記されています。

The Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University invites applications for grants to support research utilizing the Noriaki Tsuchimoto Papers housed in Manuscripts and Archives in the Yale University Library. The collection is currently comprised of 83 boxes containing materials related to the filmmaking and other activities of the Japanese documentary filmmaker Noriaki Tsuchimoto (1928-2008), who is most famous for recording the struggles over the Minamata mercury poisoning incident and other environmental hazards. The collection description is as follows:

Mori Tatsuya, the Great Togo, and Research

This is one of the more peculiar ways I’ve gotten “published.” Mori Tatsuya, the documentary filmmaker and journalist (A, A2, 311, Fake, etc.), contacted me in December asking for help with a new edition of his book, Akuyaku resura wa warau (The Heel Wrestler Laughs). Published as an Iwanami Shinsho in 2005, it was about a Japanese-American pro wrestler known as the Great Togo, who came to specialize in playing the heel in the ring after World War II, but who also traveled to Japan and was close to Rikidozan, whom he helped manage when Rikidozan toured the West Coast. Just as Rikidozan pretended to be Japanese even though he was Korean, so there were statements that the Great Togo was not Japanese, or that his mother was Chinese, etc. Mori-san published the book in 2005 without having the means or the opportunity to investigate all those stories.

So that’s why he contacted me this time. Knowing that the Great Togo’s real name was Okamura Kazuo (aka George Okamura), he did some net searching and thought he found phone numbers of relatives. He wondered if I could call those people. Knowing that such free net searches rarely come up with real numbers, I decided to do some searching on my own. (I did call the numbers in the end, and of course they were all disconnected.) Using public databases and databases through Yale, I did a lot of searching on Okamura and quickly found out a lot. (I’ve been doing a lot of genealogy research so many of these databases are familiar to me.) I did ascertain that not only were both his parents Japanese, but also that the US government treated him as Japanese and sent him to the Amache internment camp in Colorado. Perhaps because of his business or his status as a minority, or possibly to survive he did fib a bit, lying about his age on some documents, lying about his wife on a reentry document (he was first married to seemingly a Caucasian woman before divorcing after three years, after which he married a nikkei woman from his home town), and saying he graduated from the University of Oregon with a major in philosophy (I couldn’t confirm that, but couldn’t disprove it either). But it was pretty clear what his ancestry was. What also came out was how difficult his life was before WWII. His father ran a small fruit orchard in Hood River, Oregon (a town I’ve been to many times), but the local paper reports both successes and failures—and a childhood accident for George. The paper also reported that he was the first Japanese kid in his elementary school, and that the name George came from George Washington (perhaps chosen in an effort to have him fit in?). His itinerant life as a wrestler—which he started from the late 1930s—is evident from his draft card, with many new addresses written all over the edges. Interestingly, he happened to be touring in Hawaii when the war started, seemingly with his infant son but not his wife (or so says the passenger manifest of the ship).

Theorizing Colonial Cinema: Japanese Film Theory and Empire

In my research on Japanese film theory, I have always tried to complicate the concept of “Japanese” in the name of the topic. I do that not just through critiquing the desire to find the origins of such film theory in supposedly “traditional” aesthetics, but also through recognizing that “Japan” and the nation were often contested within film theory. If Tsumura Hideo or Sawamura Tsutomu conceptualized cinema in support of Japan’s “holy war,” Tosaka Jun critiqued the ideology of Japan while attempting to conceive of film as an alternative way of knowing (his resistance eventually put him in jail, where he died).

Yet one of my regrets with the anthology we produced, Rediscovering Classical Japanese Film Theory, is that we did not include any thinkers writing in Japan’s colonies or colonial spaces. We in effect reproduced the geography of the nation by picking authors who were Japanese citizens writing in Japan and in Japanese. It is in part regret over that that I did some research on some of the theory that we missed. This was occasioned by a conference that took place at Duke University in November 2016 (I remember the general funk over and the protests against Trump’s victory). My paper was, on the one hand, a continuation of my thinking about the internalization of empire that I explored in my article "Colonial Era Korean Cinema and the Problem of Internalization" (which you can read here). Was film theory in the colonies internalizing the ideologies of Japanese film theory? But on the other hand, it was also an attempt to show that we cannot discuss Japanese film theory without thinking about empire—that empire is part of the “Japanese” in Japanese film theory.

Sato Tadao sensei (1930–2022)

I opened up Facebook on the morning of March 21 and was sad to a post by Ishizaka Kenji, a professor at the Japan Institute of the Moving Image and a coordinator at the Tokyo International Film Festival. The announcement stated that Sato Tadao 佐藤忠男 had died on March 17, 2022. The Japan Institute of the Moving Image eventually put out an official announcement on its home page, since Sato was both Professor Emeritus and former president of the Institute.

Sato was one of the greatest and most influential film critics and scholars in Japan. He was always a bit different from other critics and academics, in part because he never went to college. As he always said, cinema to him was his school. He was born in 1930, and his real name is Iiri Tadao. While working at various jobs, including at the national rail company and an electronics factory, he began writing film reviews and got involved at Shiso no kagaku, an intellectual association led by Tsurumi Shunsuke, which helped define his life-long focus on the popular dimensions of modern entertainment. Working as an editor at Eiga hyoron and other publications, Sato became an extremely prolific writer, publishing over a hundred books on topics not just related to film, but also including manga, education, theater, democracy, war, literature, etc. He also wrote books for younger readers. With his wife, Sato Hisako, who was a strong presence in his work, he founded the film historiographical journal Eigashi kenkyu in 1973, and as a historian, eventually published a monumental four volume history of Japanese film (cover above). As an educator, he began teaching at Imamura Shohei’s film school, which later became the Japan Institute of the Moving Image. Sato eventually became president of that institution. He actively engaged with foreign cinema and critics, attending film festivals and conferences around the world, and serving as director of the Focus on Asia film festival in Fukuoka, helping introduce other Asian cinemas to Japan. He received numerous awards, including the Person of Cultural Merit from the Japanese government in 2019. He is the Japanese film critic who has arguably been translated the most into English, with Currents in Japanese Cinema (1982) and Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema (2011) being two book-length translations.

Writing on Obayashi Nobuhiko’s Anti-War Trilogy

Although I never intended to become an Obayashi Nobuhiko expert, I have nonetheless developed a significant connection with that utterly unique Japanese film director. It started when we invited him and his family to Yale, after which I programmed a retrospective of his work at the Japan Society. He later asked me to contribute to one of his books, and it was only a day or two after he treated my family to dinner in Tokyo that he found he had cancer. We did get to meet him and his wife Kyoko again before he passed away in 2020. I then moderated a commemorative panel discussion on him for Japan Cuts, and have begun putting together an anthology on him with Aiko Masubuchi, the former Japan Society film programmer.

So it was perhaps destiny—as well as quite a pleasure—to get a request from Adam Torel at Third Window Films to pen an article for their BluRay release of Obayashi’s anti-war trilogy, composed of Casting Blossoms to the Sky (2011), Seven Weeks (2014), and Hanagatami (2017).

As I did when announcing the Blu-Ray for Sailor Suit and Machine Gun, here is the first paragraph of my essay:

Bunka Eiga Kenkyu, Prewar Japanese Documentary, and Film Theory

Bunka eiga kenkyu, the third in my series of reprints of prewar film studies/film theory journals at Yumani Shobo, has been published. This follows the reprints of Eiga kagaku kenkyu (see my introduction here) and Eiga geijutsu kenkyu (see my introduction here).

Bunka eiga kenkyu is a bit closer to Eiga kagaku kenkyu than to Eiga geijutsu kenkyu in that it is less a film theory journal, like the latter, than a periodical by filmmakers attempting to understand their art and practice. It was actually not my first choice to do for the third reprint. The plan was to do Eiga zuihitsu, the legendary coterie magazine published in Kyoto in the late 1920s that was core to what Makino Mamoru later called the Kyoto Eiga Gakuha. But that journal is so rare, Yumani could not gather enough original issues to serve as the basis for the reprint. So I was asked to identify a substitute and had to do it quickly. I picked Bunka eiga kenkyu because, of the prewar journals that had not been reprinted and that could be reprinted without too much difficulty, it was probably the most consequential, especially in the field of documentary and debates about film realism. Yumani insisted we had to keep to the same timeline, so that did not leave much time for me to prepare materials and write a commentary. We also found out that Makino had been in discussions with another publisher about reprinting Bunka eiga kenkyu, although that publisher had done little to bring the plan to fruition. We got the okay to reprint the journal, and I asked two of the young scholars who were helping Makino’s project, Sato Yo and Morita Noriko, to collaborate by writing commentaries. So unlike the first two reprints, which just included my commentary, this one sports three. In the end, we dedicated the reprint to Makino Mamoru.

Fireside Chat about the YIDFF, Japanese Documentary, and Hanzo

The Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival was held online last fall due to the continuing pandemic. That was unfortunate, but as I had previously written about film during the COVID era (here), the pandemic had also opened up opportunities to watch Japanese film and other entertainment media remotely. The YIDFF has now jumped on the bandwagon and is running an online series of some of the best Japanese documentaries in the 30+ years since the festival began in 1989. The platform is DAFilms, which also managed the Flash Forward series, and it is offering the first week free (afterwards, I think you have to be a subscriber). Check it out here.

To go along with the series, the folks at the YIDFF have asked some involved in the festival to look back on those thirty years. Markus Nornes has written a series of illuminating pieces on the YIDFF Facebook page. The film directors Oda Kaori and Dwi Sujanti Nugraheni also recorded a conversation about the trials and tribulations of making indie docs in Asia, which is now available on the YIDFF YouTube channel (here).

Somai Shinji’s Sailor Suit and Machine Gun

I’ve long thought that Somai Shinji is the key filmmaker for understanding Japanese cinema after 1980. If long shot long takes came to dominate Japanese art films from the nineties on, it had less to do with Mizoguchi than with Somai, himself a master of the form. His cinema also left an indelible impression on me. The first of his films I saw, Moving (Ohikkoshi, 1993), left me stunned, and I still believe Typhoon Club (Taifu kurabu, 1985) is one of the best Japanese films ever. Yet in part because his early movies were categorized in the idol genre, the gatekeepers of Japanese film in the eighties did little to promote his films and even today few of his dozen or so works are available on disc with English subtitles. There have been retrospectives, some of which I was involved in. I did a panel on Somai at the 2005 Jeongju International Film Festival (my contribution to the retro catalog can be found here), and I gave a talk on the director at the Deutschen Filmmuseum in Frankfurt in 2015. These were occasions for me to think about Somai, but I still don’t feel I have a complete grasp of him. Access to his cinema remains woefully limited outside Japan.

Flash Forward Panel Discussion

A lot has been going on recentl, which I will be announcing in the next coming weeks.

To start with, I wanted to let everyone know about an interesting film series being screened online though the Japan Society in New York entitled “Flash Forward: Debut Works and Recent Films by Notable Japanese Directors” that will run from December 3 to 23, 2021. It is co-presented by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs in conjunction with the Visual Industry Promotion Organization. The series is quite unique in that it presents the work of six filmmakers lesser known in the United States by showing their debut films and then a more recent film. Some of the six are better known than others: Kawase Naomi is well-known in Europe and Suo Masayuki had a hit in the USA with Shall We Dance?. But even Kawase has had little exposure in America. The other four directors are Sakamoto Junji, Shiota Akihiko, Nishikawa Miwa, and Okita Shuichi. Since I’ve had Sakamoto and Shiota come to my classes before—here’s an old report on one of Sakamoto’s visits—and since I’ve known Kawase since her debut, the selection was a bit like a stroll down memory lane. One could argue about the selection (for instance, Suo’s debut is not Fancy Dance, but rather the pink film Abnormal Family), but it is an interesting selection of films.

Eiga Geijutsu Kenkyu and Film Theory in Japan

The second in my series of reprints of prewar film studies/film theory journals at Yumani Shobo has come out. This follows the reprint of Eiga kagaku kenkyu, the late 1920s and early 1930s journal which featured filmmakers inquiring over what cinema is (see my introduction here).

Eiga geijutsu kenkyu (Studies in Film Art) was a more heavily theoretical and academic journal, which ran for two and a half years from early 1933 to late 1935. It stood out for its quite long articles investigating conceptual topics ranging from film aesthetics to psychoanalysis and cinema. While it also devoted many pages to translations of both famous and less famous foreign theory, it was a journal that showed the confidence of its often quite young writers in critiquing that theory and composing their own ideas. That said, the journal was not necessarily revolutionary in its stance towards film theory. As I wrote in the commentary, the leader of the journal, Sasaki Norio, still had one foot in German romantic aesthetics, which rejected standard forms of cinematic realism, even as he began exploring a more sociological approach to cinema. Still, new writers such as Sugiyama Heiichi began pointing to new theoretical directions. Eiga geijutsu kenkyu was in many ways a transitional journal, indicating the shift in aesthetics as film realism came to the fore in the late 1930s.

OBAYASHI NOBUHIKO: A Call for Papers

For nearly 60 years until his death in 2020, Obayashi Nobuhiko continued to challenge and expand the many fields of moving image production he engaged in, from experimental films to commercials, from idol movies to anti-war digital cinema. While justly celebrated in Japan, Obayashi remained largely unknown abroad until Hausu, his 1977 commercial feature debut, was finally released on DVD in English-language markets in 2010 to cult success. Even then, no serious and critical engagement with his work has been published in book form either in Japan or abroad.

Obayashi is worthy of such deep study not only because his own work, with its interrogations of cinema and modern Japanese history, of youth and gender, of genre and the possibilities of the moving image, is profoundly rich. It is also because, with a career of involvement in experimental film, TV commercials and movies, major studio productions, genre cinema, independent film, and digital cinema, Obayashi is an extremely fruitful avenue for exploring different but interrelated aspects of postwar Japan’s history and media ecology. Just as Obayashi used media to explore modern Japanese history, so we can use Obayashi to explore modern Japanese media.