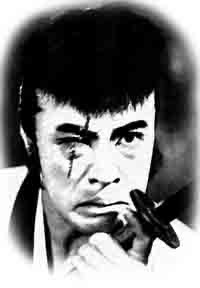

This report is about a month late, but I thought I would talk about Sakamoto Junji's visit to my Yale Summer Session class at the beginning of August. This was the second time Sakamoto-san has come to a class of mine. The first was in 1998, I think, when I was teaching at Yokohama National University. Sakamoto-san was a student at YNU way back when so when I once ran into him and Izutsu Kazuyuki at a Tokyo Film Festival party, I boldly invited him to come to my class. (This was right before Face (Kao) was released, sadly the only one of his films to be released on DVD in the USA.) Since then I have also become a fan of his producer, Shiii Yukiko, who has helped me out on a number of occasions. I have a piece in Japan Focus about Sakamoto's film Aegis (Bōkoku no īgisu), which is actually not one of my favorite Sakamoto films.

For the YNU visit, we showed one of the Kizudarake no tenshi films, but this time it was a much more difficult movie: Children of the Dark (Yami no kodomotachi, 2008). It is about trafficking of children in Thailand and was supposed to be screened at the Bangkok Film Festival until the authorities cancelled it. It stars Eguchi Yōsuke and Miyazaki Aoi and is one of a seemingly increasing number of Japanese films made abroad.

It was not an easy film for my students to watch, primarily because of what seems to be quite graphic depictions of violence towards children. Many of the questions centered around the problem of filming the other: of Japanese filming Thai, of adults filming children. Sakamoto stressed that he tried to make this a cooperative venture based on mutual understanding, where he talked with all the Thai participants so as to share the same goals. The children were the difficult part since there are some scenes of sexual molestation. First Sakamoto decided only to work with children who had never acted and talked carefully with their parents about what was involved in the scene and what the films' goals were. He made sure the kids understood what it meant to play a role. Then he filmed it such that the children would never see or touch a naked adult. Most of the disturbing scenes are then the result of editing. (Though it should be iterated that he still had to rely on some Bazinian space: there is one shot, for instance with the child facing the camera in the fore with an out-of-focus naked adult in the back. The boy probably did not see that man on the set, but the film clearly could not create these scenes without some spatial integrity.)

The students could appreciate this (though some were clearly surprised to hear that those scenes were just done with editing), but they still wondered why it was necessary to show such moments. Or why it was necessary to make this a fiction film. Sakamoto was criticized a bit in Japan for the fact that the main story line of the film, about reporters trying to stop a Japanese family from buying a heart for their dying son because the child donor will be killed in the process, is not based on any documented case. In class, Sakamoto noted that this story was in the original novel by Yan Sogil (of Blood and Bones fame), but also called it a "hypothesis," one that put together the fact that Japanese are buying organs and that there have been reports of some children being killed for organs. But he mainly stressed that this was a fiction film that was aiming to do things documentary could not. A documentary, for instance, could not show the abuse of these children, and it was precisely that dark world that Sakamoto wanted to shed some light on. A documentary would also not allow him to follow the story of Yairoon, for instance, a girl who is thrown away in a garbage bag when she contracts AIDS, but crawls out to make it back to the family home only to die. Children of the Dark, he said, was a sort of challenge within fiction filmmaking.

What I found most interesting in all this was the resulting problem of responsibility. I don't think the film ever escapes the problem of its own guilt: there are still problems in using children this way, or with Japanese filmmakers taking up Thai problems using crusading Japanese in the lead. But what is intriguing about Children of the Dark is that I believe it acknowledges this guilt. Not to give away the ending, but one of the main "crusaders" is in fact guilty himself of a previous crime, and apparently tries to help the children from his guilt. I asked Sakamoto whether he intended this to be an allegory of wartime Japan and its postwar guilt. He said that was not a primary intention, but accepted it as a possible interpretation. I think he was primarily discoursing about contemporary filmmaking, mainly taking aim at crusading documentaries or social realist films that righteously pretend to know the subject and be in a position to judge. By making a guilty film about the guilty trying to deal with their guilt, Sakamoto I believe foregrounded the inherent violence of the cinema, questioned the authority of the filmmaker and the viewer, and sought ways of still productively using that in fiction film. As he said over dinner, "Cinema is a crime" (Eiga wa hanzai da), but his quest is to see the nature of that crime and the good that might come of it. Personally, I don't think he completely succeeded in that, but it was a bold experiment in entertainment cinema that you don't see much elsewhere.

Sakamoto-san regaled us with a lot of other tales: about how little money Japanese film directors make (one colleague, who has directed five well-known films, only made about $9000 last year), or how low budgets are (Children of the Dark was about $1.5 million - a figure that amazed the students, considering how professional it all looked). He also showed us some scenes of the making of his next film, Zatoichi: The Last, starring Katori Shingo of SMAP fame. He stressed that, in opposition to Kitano's version, he was trying to return to the original. Shiii-san came along and, as usual, took charge during dinner.

It was a thought-provoking experience for all around. Thanks to Sakamoto-san and everyone at Kino, his production company, and at Waseda for this unique evening.