News and Opinion

Woman Rush Hour and Political Humor in Japan

I like a good laugh, and that is one reason I have always been interested in comedy in Japan. I wrote a book about a comedian turned film director (who didn’t shoot that many comedies), have often sought out comedy films, and even have made going to lots of yose to watch rakugo and manzai one of my goals this year in Japan. I sometimes consider it a challenge to myself, as jokes can in some cases be one of the hardest aspects to understand about a foreign culture, but it also is a way of approaching Japan from a different direction.

The manzai team Woman Rush Hour did an act on TV recently that has made me think about comedy in Japan again.

One difference that observers have noted regarding humor in Japan is the seeming lack of political satire in Japan. Although it seems that comedy in the United States, and in many other countries as well, is dominated by political humor, to the point that such comedy can be more trusted by young people for its political analysis than regular news media, there appears to be virtually none of that in Japan. I’ve read many bad explanations of that, ranging from the old claim (which I in fact encountered when I was younger) that Japanese don’t have much of a sense of humor to the Japanese-supported stereotype that such humor is not welcome in a society focused on harmony. The first is simply a product of orientalist ignorance (anyone who has been to a yose knows that Japanese comedians can be hilarious) and the second just ignores history. In fact, there have been plenty of cases of political humor from the Edo era on. Just listen to Enoken’s amazing “Is This What They Call Freedom?” from 1954—which satirizes American H-bomb tests, the Cold War “peace,” Japan’s subservient relation to the USA, the SDF, and postwar Japanese politics—and you can see there has been very biting political comedy on a popular level from long ago.

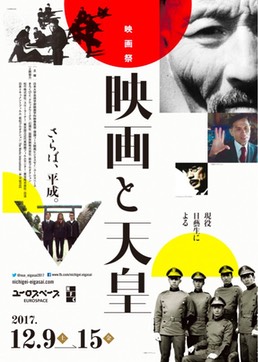

The Nichigei Film Festival: Cinema, the Emperor, and The Solitary One

In coming to Japan for this year of research, I was eagerly expecting my first attendance at the Yamagata, Tokyo, and Filmex film festivals in eight years, even if I knew their plusses and minuses. But I was also very pleased to go to a festival that I learned about for the first time: the Nichigei Film Festival, which took place in December.

“Nichigei” stands for the Nihon Daigaku Geijutsu Gakubu, or Nihon University College of Art. The study of film at Nichidai goes back to at least 1929 and has been one of the core courses of the College of Art since it was formed in 1949. The focus has been on production, with such graduates as Ishii Gakuryū, Matsuoka Jōji, Kanai Katsu, and Adachi Masao, although there are also students researching film history. Faculty have included Ushihara Kiyohiko and Tanaka Jun’ichirō.

One of the current professors is Koga Futoshi, who has had a long career starting at the Japan Foundation and continuing with the Asahi Shinbun newspaper. At both, he organized a large number of film events and festivals. He still writes a lot on film (check out his blog) and was a member of the Asahi ratings panel with me at the TIFF. After becoming a professor at Nichigei, Koga has taught a variety of courses, but quite interestingly one for third year students is about film programming. As the main assignment for the course, students have to plan and put on a film festival of their own that will show at a regular commercial theater. This is the Nichigei Film Festival. They start by having each student put together a serious proposal for a festival, from which the best are selected and presented to Eurospace, an art theater in Shibuya, which then selects the one to put on. The students then have to arrange for renting the films, creating a catalog, arranging for advertising, and inviting guests. They then have to run the week-long festival once it starts.