The film director Obayashi Nobuhiko passed away on April 10, succumbing to the cancer he had been battling for several years. He was 82.

Here is a photo I love of him with my son Ian.

Obayashi-kantoku was a guest at Yale in the fall of 2015, coming with his wife and producer Kyoko and his daughter Chigumi. They even came to our home for dinner, so the news hits me not just as a loss for cinema, but as a personal loss as well. It is in part because of such a relationship that I know we lost not just a great film director, but also a great human being.

Obayashi-kantoku was an important part of my education as a viewer of Japanese film. Like many who hit their teens in the 1970s, when Japanese cinema was supposedly in decline and rarely presented abroad, I grew up first watching the classics, from Kurosawa to Ozu to Oshima (with luckily a lot of Daiei jidaigeki thanks to the Thalia in NYC). The exceptions were the rare new films such as The Family Game (which I wrote about here) and Tampopo that earned US releases in the eighties. When I was in Iowa, probably in 1988 or 1989, I finally got to see a series of contemporary Japanese films new to the USA that was touring the country. Included was Obayashi’s I Are You, You Am Me (Tenkosei, 1982), a gender-bending film with an affectionate concern for amateur moviemaking that stuck with me. When I went to Japan in 1992 (and stayed there for about eleven years), one of the things I caught in the first year was a series of the best films of the previous year at the Bungeiza in Ikebukuro. There I saw The Rocking Horsemen (Seishun dendekedekedeke, 1992), which remains one of my favorite Obayashi films. Obayashi-kantoku, in a sense, was a core part of my introduction to contemporary Japanese cinema.

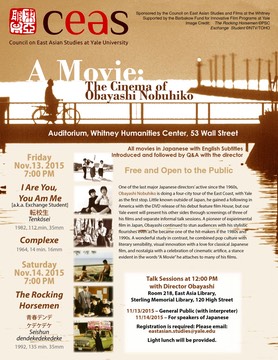

Of course, he took on other dimensions later on. While many abroad started watching Obayashi from the US DVD release of House (1977)—unearthed thanks to the hard work of Marc Walkow—I saw that rather late. I was blown away when I first saw his experimental work such as Complexe (1964) or Emotion (1966) from the 1960s, films which are still some of my favorites, not only of his cinema, but of Japanese cinema. At the same time, I could be critical. I did not write a great review of Sada for the Daily Yomiuri, in part because his romantic approach to the shojo (young girls). In class, I would show scenes from Lonely Heart (Sabinshinbo, 1985) to exemplify the complex and multivalent representation of the shojo in Japanese popular culture (to me, Obayashi and Kaneko Shusuke were the two directors offering fascinating but also sometimes problematic visions of shojo in the eighties and nineties). At the same time, he was historically a crucial figure connecting experimental filmmaking with the pop aesthetic, amateur filmmaking with commercial features. He was also constantly thinking and writing about cinema—and making that apparent in his often self-referential films. One of his many books was titled A Movie, Obayashi Nobuhiko, which was the inspiration for the title of our Obayashi event at Yale “A Movie: The Cinema of Obayashi Nobuhiko” (the Facebook page for which still lives on). His films often began with the title “A Movie."

When the chance came, I naturally jumped on the opportunity to invite Obayashi-kantoku to Yale. What I didn’t expect was the invitation from the Japan Society’s Aiko Masubuchi to curate a retrospective of his films in the week after his Yale visit (the page for that retro is here). But that forced me to delve further into his work, while also helping both events reinforce each other. I think it also thrilled Obayashi-kantoku, who put all his energy into the visit.

The Yale event, the poster for which is to the left, featured screenings of I Are You, You Am Me, Complexe, and The Rocking Horsemen. As with many of our guests, we also had Obayashi-kantoku do two talk sessions, where he discussed his experimental work, his TV commercials, his film style, etc., and took questions from the audience. As always, I had lots of support from my graduate students. The Rocking Horseman did not have hard subs, so one student had to take on the difficult task of manually advancing the subtitles of that fast-talking movie. I also did a talk session with Obayashi-kantoku for the Japan Society in New York, as well as a Q&A session after House. Here’s the video of that:

Here’s the curator’s statement I wrote for the Japan Society retrospective:

One of the last major Japanese directors active since the 1960s, Nobuhiko Obayashi is a wonderful study in contrasts. Little known outside of Japan, he finally gained a following in the U.S. with the DVD release of his debut feature film House. His work, however, is even more varied and rich than that trippy horror film. A pioneer of Japanese experimental film in Japan (for example: Complexe), Obayashi also was an innovator in the production of TV commercials and has created numerous commercially successful feature films. Working in popular genres ranging from the mystery (Reason) to the girl idol movie (The Girl Who Leapt Through Time), he never fails to make each work an exploration of cinematic form. Steeped in pop culture (The Rocking Horsemen, the film that first convinced me of his brilliance), his films are also erudite and often literary in tone. Often trying out the newest visual technologies, he also looks back on the past of both Japanese cinema, honoring masters like Yasujiro Ozu (Bound for the Fields, the Mountains and the Seacoast), and Japan itself, evoking the nightmares of war and atomic holocaust (Seven Weeks). His worldview is often defined by nostalgia (Haruka, Nostalgia or The Discarnates), particularly for a lost love, while also being consciously artificial (Sada), a stance evident in the words "A Movie" that he attaches to many of his films. Ultimately, Nobuhiko Obayashi is firmly rooted in both the local, particularly his hometown of Onomichi (I Are You, You Am Me) and the past, but his adventure in cinema is, we can say, universal and still very contemporary. Such contrasts have made him both fascinating and complex--one of the most bountiful of Japanese filmmakers.

What I most learned from Obayashi-kantoku’s visit was about him as a human being. There was a bit of the sixties in him, such as his repeated signing “I love you”, but that was always founded in a firm dedication to peace; while often making fantasy films, he staunchly believed that cinematic wonder offered its own important vision of historical reality.

In the end, I was most impressed with his relationship with my son. When we invited him and his family over to our house for dinner (photo to the right), my son insisted on showing him the 13-minute video he made for his high-school history class lesson on the Vietnam war. This is the description of that which I wrote up for Obayashi’s book, Itsuka mita eigakan (which I introduced here):

イエール大学に監督を招待した折りに、ある晩大林一家を我が家に招いた。巨匠の来訪に調子に乗った高校生の息子が、前学期の歴史の課題で撮った「ベトナム戦争映画」を監督に見せた。 『地獄の黙示緑』に似て非なる13分ほどの初ビデオ作品は、技術的な問題が山盛りであった。例えば、3人で作っていたので、殺されるベトナム兵を全員息子が一人で演じる等。作品を見た監督は優しい褒め言葉を息子に下さっただけではなく、次の日のワークショップにも、そしてその晩の『転校生』上映後の質疑応答にも、その映画を例に取り上げて下さった。技術的な欠点は、それを被せるよりも、むしろ息子のようなアマチュアは自らのリミテーションを認識して、それを利点に転ずることができたなら、それはプロの作品にも劣らない立派な「映画」になりうる。大林監督の人格のみならず、監督の「映画」の哲学がしみじみと伝わってきた忘れ難い貴重な体験となった。

Basically, my son’s film was a no budget version of Apocalypse Now, in which not only did Connecticut backyard lawns and forests look nothing like Vietnam, but my son played all the Vietcong who got shot. It was full of technical problems, but Obayashi-kantoku not only praised the film, he referenced it in the talk session and in the post-screening Q&A the next day. He told my son—and the audience—that if an amateur film does not try to hide its limitations, but rather acknowledges and takes advantage of them, it can be as much a splendid example of cinema as Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Such a philosophy surely supported his early movie making, as well as represented the thinking of the amateur film world of the sixties to the eighties. But it also showed both his kindness and his profound skill as a teacher. My son was deeply impressed.

The next summer, the Obayashis invited us and Aiko to their favorite tempuraya in Futakotamagawa. My wife couldn’t make it, so it was just my son and I. That’s when I took the above picture. I love that photo: you can sense both Obayashi’s warmheartedness and my son’s comfort, even though he’s sitting next to one of the world’s great filmmakers.

I’ve heard it was only a couple days after that that Obayashi-kantoku was told he had cancer. My sense is that that diagnosis, which would have disheartened most people, was a call to action for Obayashi-kantoku. He made the brilliant Hanagatami while undergoing therapy (the last time I met him was at a screening of that film at the FCCJ). He then directed another film, Labyrinth of Cinema (Umibe no eigakan—a review here), that was actually scheduled to open on the day that he died (proving again his life and cinema were linked), but has been postponed due to measures against COVID-19. I can’t wait to see it.

Obayashi-kantoku’s death in some ways does not seem real. Perhaps it is just another of his movies, another reel in a life dedicated to film. But it is a fantasy that, like all his fantasies, has its own reality. And like his life and his films, it is profoundly moving. As a human being, Obayashi-kantoku was in the true sense of the term, a movie man, a man who moved many with his films and his character.