My excuse for the long break between posts is that I was on a tour of Japan. I wish it was to promote my new book, Visions of Japanese Modernity, but authors of obscure academic texts do not get book tours. Rather, I was serving as a study leader on a tour of Japan organized by a division of the Association of Yale Alumni called Yale Educational Travel. They basically organize tours all around the world that are led by Yale professors, who give lectures along the way. They can be a great way to do more than just sightsee, and they help keep alumni in touch with the university's educational mission and remind them about their alma mater (it does not take a genius to figure out why many major universities organize such things).

This was the second time I have done this tour. It basically involved doing a circular trip around Japan, mostly on a cruise ship called the Clipper Odyssey, starting in Tokyo, moving to Sado Island, Kanazawa, Matsue, Hagi (and then a brief trip to Korea to clear Japanese carriage law), Hiroshima, Miyajima, Kurashiki, and then ending in Kyoto. To fill the ship, other institutions such as Princeton, Stanford and the Smithsonian also participated, and so I shared lecture duties with such fine people as David Leheny, Mark Peattie, and Marjorie Williams. I talked about the historical geography of play in Tokyo, representations of the atomic bomb in popular culture, and the Kyoto's centrality to Japanese film culture.

Such tours can be a fascinating but also somewhat surreal experience. Tourism can be out of this world (or at least the everyday world), which I strongly felt whenever I tried to find a newspaper at the tourist spots (they can't be found). There is much that can be said about the politics of tourism, but such educational tours can, with the right study leaders, provide an opportunity to be self-conscious of that. For me, it is great to get out of the academic world and talk to people I normally do not teach (which is a learning experience for me as well). We had a very inquisitive group, with many different perspectives (Hiroshima is difficult to teach when almost everyone is over 65), although the cost of the tour made it demographically less diverse. I enjoy these tours a lot (and with the clout of their money, they can do some things I could not do alone even after all the time I have lived in Japan), but they are a lot of work.

As usual, I cannot travel without thinking about movies in one way or another. This time, I noticed some movie theaters in peculiar, if not also ominous places.

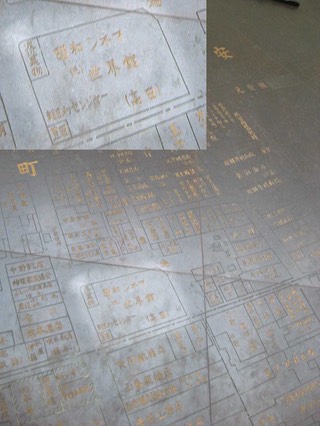

The first was in Matsue Castle. Like many castles in Japan, the floors to the top often contain a variety of exhibits about the locality. Matsue's has several models showing this small, rural city in different decades. I could not help but take a photo of the model of downtown Matsue in 1959, during the heyday of the moving picture business, showing some of the theaters such as the Matsue Toei, the Toei Daigeki, and the Matsue Nikkatsu. I think the Boatopia Matsue, a betting parlor for the boat races, is now where the Matsue Toei used to stand.

The second was in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which memorializes the dropping of the atomic bomb. It is hard to think about movies in such circumstances (although, as I emphasized in my lecture, portions of which were based on my article in In Godzilla's Footsteps, the cinema has been an important means of thinking through the bomb), but wartime Hiroshima, like any other Japanese city of the time, had movie theaters. In a large plaque at the end of the exhibit, you can see the city layout and thus notice that there was one movie theater, called the Showa Shinema (formally called the Sekaikan), which was probably only about 500 meters from the hypocenter. I believe it was located right about where the Cenotaph in the Peace Park is now. I highlighted and inserted a detail for the photograph I took. You can see Motoyasu Bridge on the top left of the photo.

So in one case, a cinema is replaced by a boat racing betting parlor; in another, by a monument containing the names of the dead. History moves in unusual, ironic, and also sometimes tragic ways.