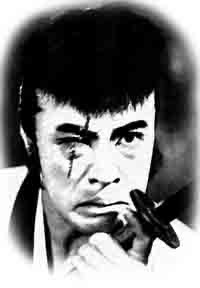

An English translation I did of one of the Japanese film director Aoyama Shinji’s major writings on film, "Nouvelle Vague Manifesto; or, How I Became a Disciple of Philippe Garrel,” has finally appeared in print in the sixth issue of LOLA, the online film journal edited by Adrian Martin and Girish Shambu.

- Aoyama Shinji, "Nouvelle Vague Manifesto; or, How I Became a Disciple of Philippe Garrel,” LOLA 6 (December 2015).

The article is accompanied by a short introduction I penned that explains the manifesto’s basic points and its historical place.

- Aaron Gerow, "Introduction to ‘Nouvelle Vague Manifesto,’” LOLA 6 (December 2015).

I want to thank Aoyama for not only allowing me to publish this, but also for helping me find the citations for the many quotations in the piece. I also need to thank Adrian and Girish for publishing this. I did the translation years ago—and Adrian expressed interest in it years ago—so I apologize for the delay, even if some of the time taken was necessary.

Aoyama’s manifesto was published in 1997, right when he debuted as a director, and represents his thoughts on his positionality and future direction. While the manifesto never became the defining document of an organized film movement, I argue that it helps us understand not only Aoyama’s cinema, but also an in certain ways representative intervention in the cinema world at the time. As such, it can help us comprehend one definition of a politics of film style (the use of the long take, the rejection of image as representation, etc.) and how that relates to the politics of post Cold War Japan (the problem of the individual, the problem of the Other), especially in contrast to the political modernism of the 1960s New Wave. Along with Aoyama’s later essay, “The Geography of Cinema” (Eiga no chirigaku), published in his essay collection Ware eiga o hakkenseri (Seidosha, 2001), the manifesto is one of the major theoretical contributions of the time. I have used it not only in my article on Aoyama in Yvonne Tasker’s Fifty Contemporary Film Directors (Routledge, 2010), but also in my book on Kitano Takeshi.

This translation and introduction are just one part of my larger project of studying and introducing the history of Japanese film theory, which has included such projects at the special issue of the Review of Japanese Culture and Society. As such, Aoyama’s manifesto should be read as not just a key for thinking about 1990s Japanese cinema, but as one manifestation of thinking about cinema and media in the world at the end of the millennium.