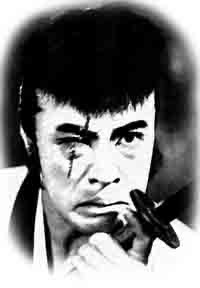

The great actor Shishido Jo has died. When I was in grad school, he was virtually unknown abroad, but that was because the films of Suzuki Seijun and Nikkatsu Action were largely ignored in foreign festivals and markets since such supposedly crass popular cinema was not what the gatekeepers liked. When Seijun finally came to be celebrated abroad, Jo started garnering attention, but it is was not because he was an art cinema actor in the line of Nakadai Tatsuya, or a popular film star like Ishihara Yujiro (who is still not well-known among foreign fans of Japanese cinema). He was a unique character who transcended those cinematic categories. In that way, he somewhat resembled the nonconformist Seijun during his Nikkatsu days, but Jo’s character was his own and was visible in many non-Seijun films.

Jo was cool. He was cool even when he played the bad guy, which is why his villains were never just bad, but often shared much with the cool hero, especially a certain professionalism. In Plains Wanderer (The Rambler Rides Again, 1960), he does some pretty awful stuff, but you can’t hate him, even before the series narrative demands he team up with the hero at the end. That complexity made it possible for him to be both comedic and tragic, sometimes with a touch of insanity that Seijun brought out well in Branded to Kill (1967). It was rarely realistic, as it was an often self-conscious complexity, with Jo sometimes playfully (Hayauchi yaro, etc.) or sometimes contemplatively (A Colt Is My Passport) performing the possibilities of the character “Joe the Ace.” He was a serious actor, famously even going so far as to implant silicone into his cheeks to better play the part of a baseball catcher, but that seriousness could sometimes mysteriously blend with self-parody. Jo was one of a kind.

His film work itself has earned him a special place in my understanding of Japanese film history, but I also had the pleasure of doing an event with him back in 1999. It was not only a special chance to get to know Jo, but also my first opportunity to really experience what a Japanese movie star is. Jo is not just Joe, he is a star.

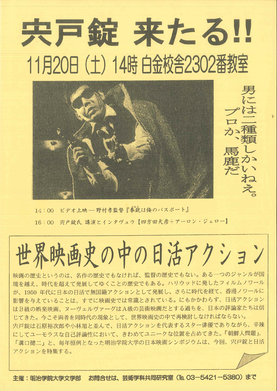

Back when I was teaching adjunct at Meiji Gakuin University, the professor and critic Yomota Inuhiko organized a one-day event entitled “Nikkatsu Action in World Film History” to be held on November 20, 1999 (see the poster above). The program basically consisted of a screening of A Colt Is My Passport, followed by a discussion between Jo, Yomota, and me. But this was Jo, so it had to be something more.

He came with a costume—a sleek, gangster-like suit—into which he changed before going to the event space (a classroom). And he came with a gun—a fake one of course. When he came on stage with the gun in a hidden holster, he put on a performance, turning his back to the audience before turning suddenly and firing the gun at them! Of course, everyone loved it.

He seriously engaged with the questions Yomota-san and I posed. My memory of the content is fuzzy after all these years, but I recall a number of our conversations. One was about his tendency to appear in Japanese Westerns: the studio even billed him as the “third-fastest draw in the world” (number one was Audie Murphy!), a number that was definitely made up but probably appeared more accurate for not claiming the one or two spots. Jo was actually listed as the co-author of a 1961 book entitled The Gun and the Western, but he said he didn’t do anything for it. The most memorable discussions centered on the studio system. We showed A Colt Is My Passport because it was his favorite film, but he confessed he was so busy in those days, he rarely got to watch his own films; Colt was one he watched and liked very much. At the time of the event he was preparing a novel entitled Nikkatsu Studio (which eventually came out in 2001). He was an actor who recognized how important the studio system was to his art, and wanted to relate and preserve some of that world in the novel. I remember remarking how his on-screen repartee with Kobayashi Akira or with Akagi Keiichiro appeared so smooth and engaging—so coolly professional—and felt how it (as well as the professional ethos of Nikkatsu Action characters) was a product of the studio system. Jo agreed: they rarely had time to rehearse, so that repartee was the product of seemingly dozens of on- and off-screen encounters over the years.

I mentioned above that doing this event with Jo was one of my first encounters with stardom in Japan. What I experienced before and after the talk brought that home. First, I accompanied Jo as we moved from the Department of Art office to another building where the screening had just finished. Meiji Gakuin University has a high school attached to it, and there used to be an athletic ground in the middle of campus that we had to pass in order to get to the other building. It just so happens high-schoolers were out on the ground that day and, boy, did they react when they saw Jo! While probably none of them had seen a Nikkatsu Action film, Jo was still a major star on TV and they screamed and shouted and ran over to try to shake his hands. Wow, I realized: a star is a different kind of person—or is at least treated as such.

But Jo also treated us as a Japanese film star does. After the event, Jo invited some of the core organizers over to the izakaya near his office. He got quite drunk, and I remember him asking me for advice on whether to accept the role of Aoki Morihisa, the Japanese ambassador to Peru during the time of the Japanese embassy hostage crisis, in a TV movie or film on the incident. We did consume a lot that evening, and Jo insisted on paying the tab. The fact was that, even though he could have commanded a much better fee some other place, he agreed to appear at Meigaku for only ¥100,000—and then spent all of it on us eating and drinking afterwards! (I remember the master of the izakaya taking us aside to that we could secretly pay off the amount that went over ¥100,000 without Jo knowing). That is what stars did in the days of the studio: not just partying hard, but insisting on treating everyone even if it meant using up all the money they made that day. Stars had to play a certain role even outside the studio gates.

So to me, Shishido Jo was not just a great performer—the character Ace no Joe—he was a real movie star. And probably the last of his kind I will ever meet.